Arizona: Skipping Classes to See the Southwest

- Jul 18, 2025

- 8 min read

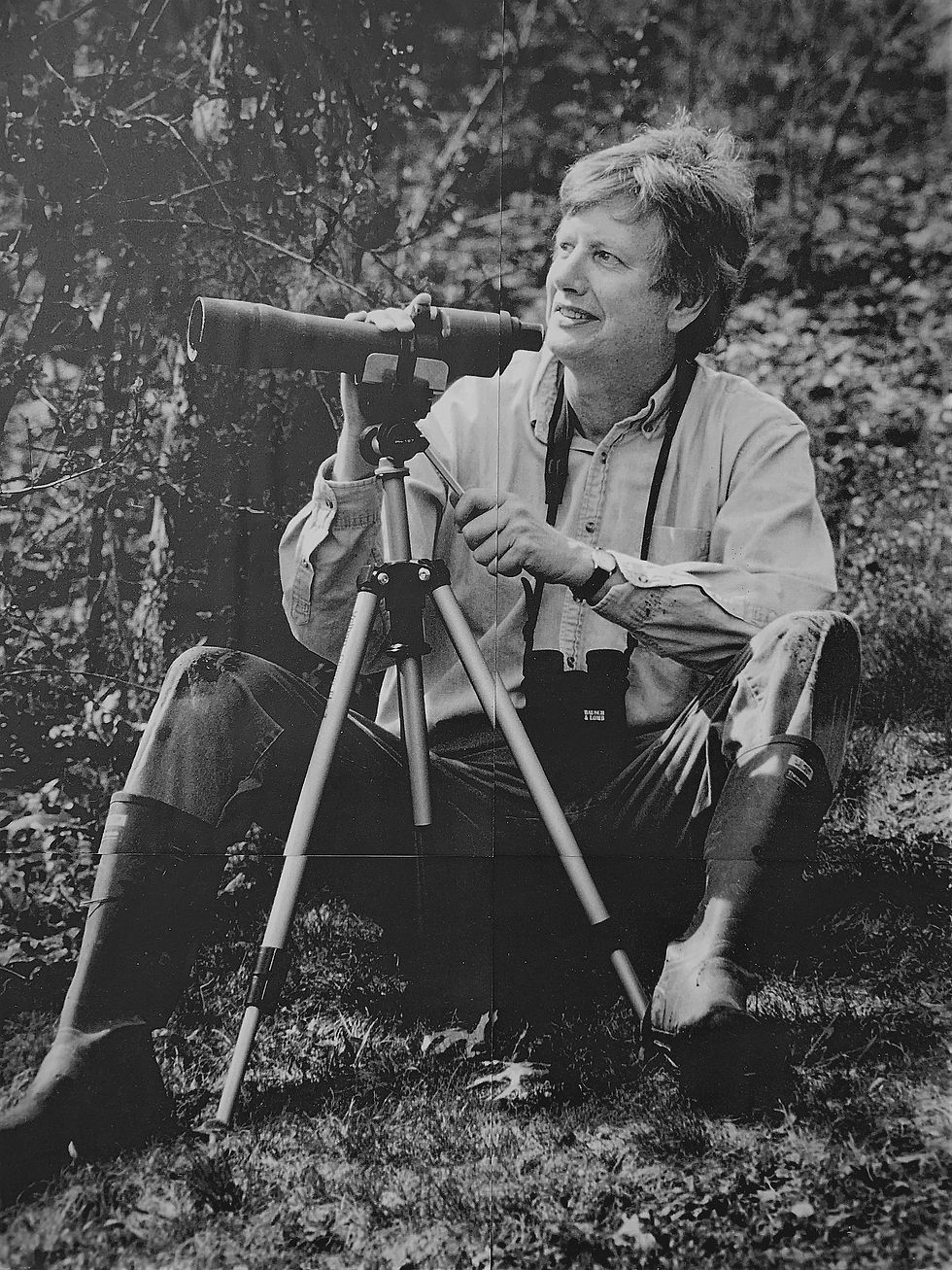

An excerpt from Peter Alden's upcoming memoir.

Choosing Arizona instead of New England for my college destination, I was guaranteeing that I wouldn’t know a single soul when I arrived on campus. I made my way west, three thousand miles from home and just north of the Mexican border. Freshmen were required to declare a major right away. With ornithology as my greatest academic interest, I chose the closest major to that field – zoology. But looking at cells under microscopes, studying diseases and various invertebrate body parts, left me totally uninterested. After I flunked my midterm exam in zoology, the professor called me into his office and said, “You're breathing air that a real student could be breathing.”

I switched my major to geography and never again took a single course in zoology. I didn’t want to be bound to a lab or library. I was drawn to see and experience the animals in the wild, their biology, behavior, and interactions with their ecosystems. Having gone on to write sixteen books on bird life with four million copies sold, I would conclude that the change in majors was not such a disadvantage.

In Arizona, I joined the Tucson Audubon Society. The club president was a university professor named Dr. John Schaefer. We hit it off right away. He was only fifteen years older than me and later became President of the University of Arizona Society. In the fall of my freshman year, I joined John Schaefer and some other hardcore birders for a trip into Mexico, a destination that would lure me back countless times in the years that followed

By the time the spring semester at the University of Arizona began, I’d seen most of the birds of Arizona. I learned about an overnight train that left Nogales and traveled down the entire Pacific Coast of Mexico, headed for Guadalajara. Nobody was birding in that part of Mexico back then. There wasn’t even a field guide with color pictures for Mexico. I decided I wanted to find out what I could see there.

It soon became a regular routine for me. I couldn’t afford hotels or restaurants, so I packed a tent, a sleeping bag, and a six-pack of Campbell’s Scotch Broth. The train was cheap and every month I’d disembark at a different river valley in western Mexico. I’d roll-out my sleeping bag wherever I found a quiet secluded spot and spend the days looking for birds. My first stop was in the state of Sinaloa, now known for its drug cartel. I went farther south with each monthly trip, all the way to Mazatlán.

Each trip brought with it a different adventure. One night while sleeping under the stars near a riverbank, I awoke in my sleeping bag to the sensation of rain. Even in my drowsy state I knew that didn’t make sense: it doesn’t rain in February in western Mexico. No, in fact it was a cow relieving himself. Other times wild dogs found me and started barking. One day as I waited for the train north, I spotted some women selling tacos and enchiladas. I was hungry, weary of my usual fare of soup I bought a couple of tacos and wolfed them down just before the train pulled up. We were passing over a river when my stomach started to act up, and the next thing I knew, I was losing my tacos into the river. From that experience I learned to be much more careful with street food.

I was fast becoming something of an expert on the birds of western Mexico, and I was garnering attention in other ways too. I was Tucson Audubon’s only student member. All the other members were in their sixties or older. I was spry and agile, and I knew so many kinds of birds already. When we went on bird walks in the mountains, I was always spotting birds that no one else had seen. One time in Patagonia, just twenty miles northeast of the border, I saw a Green Kingfisher, Montezuma Quail, and numerous other interesting birds I had never seen before.

That spring, the chapter had an election and I was asked to be vice president. It was quite an honor for me: three thousand miles from home, just a few months into my first year of college, and taking on a leadership position with a major Audubon Society chapter that had hundreds of members.

In the fall semester of my second year at the university, Tucson Audubon hosted officers from National Audubon in New York on a visit. We’d learned that the president, vice president, and U.S. officers of National Audubon were looking for a location to hold their first western U.S. annual meeting. Representatives from Audubon chapters around the country would gather. Previous annual meetings would offer pre- and post-conference trips.

I immediately spotted an opportunity. All the train rides I’d taken the previous spring south into Mexico had given me a very good lay of the land. And there was a businesswoman from Nogales named Caty Noble who was also a member of Tucson Audubon and would be good with the logistics. Joining forces to pool our talents, we put together a proposal for a tour on which she would rent the bus, reserve the hotels and handle registrations and other office work, and I would be the birding guide. No one else was running tours to Mexico at that time, and National Audubon was happy to take us up on our offer.

Much to our delight, once we advertised it to the prospective conference-goers, we filled up not one but two tours. I had to plead my case with my professors, telling them I’d be missing two weeks of classes, but in those first two tours I made several thousand dollars – a far cry from the five-dollar-a-week allowance my parents had been sending me. With the money, I bought a used Austin Healey which would enable me to travel farther south into Mexico and all the way west to California, and home to Concord for the summer.

After the success of the trips for National Audubon members, Caty Noble came to me with an idea. She pointed out that Tucson Audubon had taken twenty-five percent of our profits from those trips and suggested we start our own tour company. Given how well we’d worked together on those first two efforts, I agreed it was worth a try, and we turned out to be a good team. She was excellent with logistics; I drew people in with my expertise about birds, animals, and ecology. We called our endeavor Mexico South Tours. I led tours for our new company for the remainder of my college years and beyond.

My biggest challenge during those years was completing my college courses. The general rule at that time was that if you missed an entire week of classes, you’d be thrown out for the remainder of the semester. I tried to plead my case with my professors, telling them, “My family doesn’t have a lot of money. I’m out here supporting myself as a birding guide and serving as vice president of Tucson Audubon.” Rather than dismissing me for my frequent absenteeism, my professors were impressed by my intrepid spirit. So many of the young men at the University of Arizona did little more than chase ladies and indulge in fraternity parties. By demonstrating to them that I had come to their part of the country all the way from Massachusetts and was now earning money leading tours to Mexico, I earned their admiration. they agreed to overlook my attendance problem.

All the same, even if I wasn’t sitting through every lecture, I still had to pass the exams. I soon gleaned two strategic insights. First, the campus library archived previous years’ tests. I figured out that eighty to ninety percent of all of the questions on the exams were repeated, and that most professors didn’t want essays. I'd go through and memorize the last four or five years’ worth of tests for each of my professors, and just as I predicted, most of those same questions came up when I eventually sat down to take the exam myself. Second, I learned that less than two percent of the questions had to do with any of the suggested outside readings. But this latter point meant that class notes were of paramount importance. Early in the semester, I would attend my classes and be sure to take impeccable notes. If a classmate mentioned having to miss a class meeting, I’d offer to give them my notes. When they thanked me, I’d slip in, “Listen, I'm going away for two weeks. Can I read your class notes when I get back?” In that way, I managed to graduate from college with a B average, and the occasional A, despite being away from the campus four to five weeks per semester. I finished my bachelor’s with a major in geography with minors in anthropology and Latin American Studies.

I graduated during the height of the Vietnam War. The U.S. government was drafting just about anyone who could possibly serve, regardless of their fitness for duty. When I wasn’t leading tours, I was making scouting trips, now beyond Mexico into Guatemala and farther south into Latin America. The draft board required that I update them constantly of my whereabouts. I had tours to lead and places to scout all spring, so I sent change of address postcards every week by snail mail to buy myself 4 months free. Finally, I returned to Concord in June to visit my family and undergo a draft physical in Boston.

I showed up as required to the physical and mentioned that I had some problems with my shoulder, which had been dislocated numerous times during high school football and basketball games. The examiner in charge of the physical brushed that off, assuring me that if my shoulder fell apart in basic training, the Army would compensate me sixty dollars a month for the rest of my life. That wasn’t a trade that I was willing to make, and so I decided to challenge my acceptance by getting my family doctor involved. Our doctor, by chance, was the draft board examiner for the Concord area. He had reset my shoulder numerous times, including the first time I was carted off the football field. However, I needed to get another testimony on the shoulder issue. So, I went to my high school football coach. He was a neighbor of mine, a nice Catholic man who played Notre Dame fight songs all the time and had fought at Iwo Jima during World War II. He listened to my concerns about my shoulder injury but declined to help, saying that he believed the Army would be good for me.

I then went to Coach Hayes, my basketball coach, a great guy who had played with Bob Cousy of the Boston Celtics at one time. Coach Hayes was a Democrat who didn't like the Vietnam War very much. Upon learning of my predicament, he canceled his class took me to a Notary Public, in Concord, and declared to a clerk, “Mr. Peter Alden suffers from a severe history of constant shoulder separations, and I feel that he really would not make it in the U.S. Army.” I took his document and the doctor's document to the draft board, and they told me I was medically discharged. Within forty-eight hours, I was on my way to Europe, where I would spend the rest of the summer on a quest to see new birds.

Comments